My short description of the Islamic Manuscripts & Rare Books at Lane Medical Library, Stanford University Medical Center has been published here in Avicenna, The Stanford Journal on Muslim Affairs

My short article on Manuscripts and Rare Books from South Asia available online

I recently wrote a short piece for Dabba, Stanford University’s South Asia Magazine. My piece is titled “Manuscripts and Rare Books from South Asia at Stanford’s Lane Medical Library”. The magazine is available online and can be accessed here.

Some Notes on Pre-Modern Islamic Medicine

The Persian medical manuscripts I deal with at Lane Medical Library often contain recipes and prescriptions for various diseases. The MS themselves include materia medica (mufradat), medical dictionaries, pharmacopeias (qarabadin), manuals of diseases and cures (amraz and adviyah), diet (makul wa mashrub), prophylaxis (hifz-i Sihhat) prescriptions (mujarrabat), and natural histories.

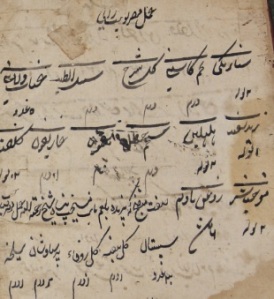

Browsing through the notes scribbled on the margins and the flaps of the books, I have discovered the important role of measures and weights in these recipes. Certainly, the weights of an apothecary varied across the Islamic world and depended on the local/regional prescriptions for units of measure. These Persian medical MS of Indian origin or provenance include Persian and local Indian measures. I am as yet not aware of study which can provide exact modern translations for these weights, so here are some descriptions with rough modern estimates:

The standard measures include

ratl (رطل)ِ, which translates to roughly 3 kg

uqiyah (اوقیۃ) , which translates to roughly 250 grams

tola (تولہ)، which translates to roughly 11 grams. This is a typically Indian unit of measure.

mithqal (مثقال). which translates to roughly 4.25 grams

dirham (درھم), which translates to roughly 3 grams

habbah (حبۃ), which translates to roughly .64 grams (66 habbah equals 1 mithqal)

Along with weights, there are a variety of interesting ingredients used in these recipes.A few novel (from our modern world-view) ingredients are:

the milk of a woman

the horn of a goat (qarn al-ma’izْْْ/قرن الماعز)

the horn of an antelope (qarn al-ayyil/قرن الایل)

these horns are sometimes heated and burnt.

In one article, Dr. Savage-Smith lists in detail some of the weights and measures used in pre-modern Islamic medicine. She also attributes the earliest use of Western and Latin chemical analysis and disease-specific cures to the Ottoman physician Ibn Sallum (d.1081/1670).

see: Savage-Smith, Emilie. Drug Therapy of Eye Diseases in Seventeenth-Century Islamic Medicine: The Influence of the “new Chemistry” of the Paracelsians. Madison, Wisc: American Institute of the History of Pharmacy, 1987.

Using Digital Humanities Tools (Palladio, Stanford) for the Persian Medical MS at Lane Medical Library, Stanford University Medical Center

Palladio is a very useful DH tool developed at Stanford University. You can read more about it here

I have been using DH tools and Palladio in particular to map some of the Persian Medical Manuscripts at Lane Medical Library, SUMC. There are around 30 MS but in this case I have used the metadata from only 18 texts. I was interested in a mapping and graphing a few categories across these texts; besides important descriptive information (call numbers, titles), I added these categories:

Place of Copy (with proper GIS coordinates; mostly Persianate cities)

Script (nastaliq, taliq, ruqu’ah, shikasta, and Indian nastaliq)

Date of Origin (between 1100 and 1880 CE)

Date of Copy (between 1300 and 1880 CE)

Subject (mostly medicine; some natural history)

Dedicatee (kings, patrons, doctors, European patrons)

Palladio provided some very interesting results where the metadata from these items could be mapped and graphed.[I also made a Google Maps of the MS; see below, Feb 17] I am interested in a larger research question: how do scripts change across space and time in this small collection? how can the creation (original) and copying (extant copy) be mapped in terms of time? what can be said about the relationships between particular cities (Isfahan, Delhi, etc.) and scripts (Nastaliq, Ruquah)?

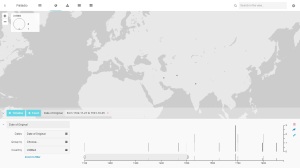

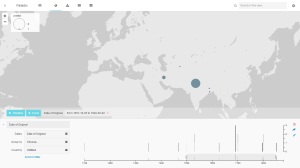

Palladio does not allow for a direct link to the user interface; meaning that I cannot provide direct access to the maps, tables, and graphs that I see after I input the metadata. But here I have added some screen-grabs from Palladio:

1. The image above indicates simply the cities in which the MS originate (but were not necessarily copied). From West to East, you can see Diyarbakir, Tehran, Isfahan (the second largest point), Herat, above that Bukhara, Delhi (the largest point in size), Malda, and then below it Kolkata. Most of the Persian Medical MS, then, originate in Delhi.

2. The image above traces the cities of origin of each MS (where it was originally written) between the years 1100 and 1500 CE. You can see that Isfahan, Herat, and then Delhi are only cities which have produced items before 1500 in the Lane Medical Library Persian MS collection.

3. The Image above traces the cities of origin of the MS originating between 1500 and 1850 CE. From West to East, Isfahan, Bukhara, Delhi, Malda, and Kolkata are the cities traced.

4. An important question the the popularity of scripts across time and space. Here we see that the Ruquah, Shikasta, and Indian Nastaliq scripts predominate in the MS from India (Delhi). Nastaliq cannot be ignored, as it is ubiquitous and very popular across time and space. The Iranian MS have a strong preference for Nastaliq script; this graph displays the entire MS collection.

More complex research questions can be asked of this material and I intend to make use of other aspects of Palladio in the future.

Marginal Notes Between Manuscripts and Lithographs

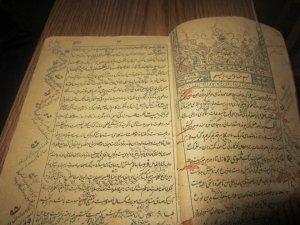

Between Manuscript and Lithograph one major difference can be observed: the disappearance of marginal notes. My observations have emerged from consulting a small collection of private items that originate in Muslim South Asia which contains manuscripts, lithographs, and notes from a period spanning three generations of a single family of scholars.

In manuscript codices ample space is provided on the page for notes, in most cases. One can observe the owner of the codex reading and commenting on the item and expressing his engagement with the text. The codex is constructed with the intention of making it interactive and a ‘living’ and ‘fluid’ space for the expression of the observations and thoughts of the reader. The ‘original’ textblock is not the only text that the page is intended for–the marginal notes and observations of the reader are considered to be part and parcel of the identity of the text and add to its identity and to its transmission. Scholars and readers can be seen making important notes, adding glosses and commentaries, and editing the ‘primary’ textblock. These two sets of writing constitute what can be considered as holistic and original in one single MS.

Lithographs, on the other hand, present an entirely different picture. In print, the primary textblock becomes somehow removed and distant from the pen of the reader; what appears in print is given its own space and is rarely edited or commented upon directly on the page. The texblock moves from being primary to being ‘original’ and occupying a place of privilege, without the reader being provided the space for commentaries and notes on the page. This indicates that the reading practice changed between MS and Lithograph; this certainly did not happen overnight and dramatically. It seems that when lithographs first appeared (photo below) they did not provide space for marginalia but were accompanied by particular glosses or commentaries. One could now purchase texts with commentaries of famous figures, for instance. But, one could was not provided space for his or her own additions to to the notes of previous scholars on the page. This would not allow space for direct engagement with the primary textblock–it has now become ‘original’ and somehow privileged, untouchable. It is not that readers did not continue to read and engage with the text; it just that they did not do so on the page itself.

In this particular private collection spanning the late 19th to the mid-20th century, manuscripts contain notes made by the scholars who owned them. Subsequent generations now have lithographs of other works in the same field and these lithographs now contain loose leaves of paper with elaborate notes on them. These loose leaves are inserted between the pages where the primary text with which the notes engage are present. The development of portable and bound notebooks does not occur in this particular collection until the late 1930s.

Google Map of Persian Manuscripts at Lane Medical Library, Stanford University Medical Center

For the past few months I have been working on a set of Persian MS at the Lane Medical Library. The library’s archives contains a number of MS in Persian; most are on medicine and are of Indian provenance or origin. I was able to map most of them and provide descriptive information; research still needs to be done on the historical origin of these items but at least I have a framework and map to work with. I do need to add other descriptive categories through which I can display data, including scripts, types of paper, specific subjects, and places origin. but for now, enjoy!

Types of Papers in Persian MS

There is almost an endless variety of paper used in Islamic MS; Persian MS also reflect the diversity of paper sources and types of paper available in the pre-modern market. Pre-industrial paper was made from a variety of ingredients and called for a complicated process; suffice it here to say that linen (flax), hemp, and other plants provided the pulp for paper. Pre-mechanical manufacturing basically provided two categories of paper:

A. Wove paper. this was made with a cloth sieve (in the Islamic world) and later on with a fine mesh (in Europe). In the Persianate world, wove paper was replaced by laid paper before the early modern period. In the 19th century, Iranian MS indicate the growing popularity of European wove (and laid) paper.

B. Laid paper. This was made from a sieve–either wooden or metallic–which had the ability to be re-used with subsequent sets of paper. This type of paper was used in the Persianate world for the longest period in history.

I have found at least four (4) different types of paper in Persian MS I’ve been looking at. Here I list them in order:

1. European laid paper, usually with chain and laid lines. Appears in MS from the late 18th century.

2. European wove paper. This appeared on the market in the 19th century; shows up in a late 19th century MS from Isfahan, Iran.

3. Persian wove paper, used very early on until the twelfth century CE. The use of wove paper declined in favor of laid paper due to the arrival of laid molds on the scene; cloth sieves used to make wove paper were not disposable and easily re-usable (at least that is what some scholarship suggests, but I am a little skeptical).

4. (most likely) Indian paper with laid lines visible. There are barely any chain lines in Indian or Persian paper due to the mold used.

Here are four samples:

****watermarks are complicated enough and warrant their own entry (coming soon)

Elaborate Titles in 18th Century India

This particular MS (Zafar Namah Shawkati, Lane Medical Library Z306(I)) is very beautiful; it was written in Nastaliq script and contains a variety of small and elegant decorations. It was copied by a single copyist and shows a calm and elegant hand.

The MS, titled ‘Zafar-Namah Shawkati’ (Lane Medical Library Z306) was copied by a Muhy al-Din Pandui in honor of certain important British military figures. It was written sometime at the turn of the 19th century in Calcutta, India. At the time Calcutta was a city from which the British extended their military and political presence in India. The (in) famous Lt. Col. James Achilles Kirkpatrick (1764-1805) makes an appearance as an honoree as well, along with General Sir Robert Abercromby of Airthrey (1740-1827). The Muslim Nawab Ghulam Muhammad Khan Bahadur of Rampur (1763-1828) is mentioned along with Abercromby. The work recounts the military and political conquests of the British in some detail.

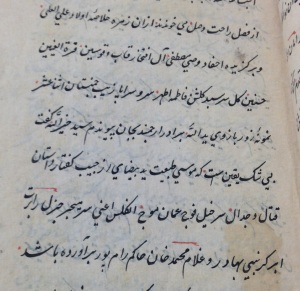

The image above contains a few elaborate titles bestowed upon Abercromby and the Nawab. Here I’d like to translate them and explain some terms in parenthesis:

“Chosen of the Descendants of the Household of Mustafa, (from) the Family of the Glorious Jewels (lit. necklaces and arches), The Light of the Eyes of the Hasanayn (i.e, al-Hasan and al-Husayn), Chief Rose of the Garden of Fatima, The Total Adornment of the Constellation of the Twelve (i.e, the Twelve Shi’i Imams), Exemplar of the Strength of the Hand of God (i.e, Ali), My Dear Elder Brother ٖFastened to My Heart, ??…there is little doubt that like Moses, (he) produced an illuminated hand from stories (?) of violence and conflict, Chief Rider of the Illustrious Army, (the) English, I mean (none other than) Sir Robert Abercromby Bahadur (honorific) and Ghulam Muhammad Khan, the Ruler of Rampur”

Classifying Multiple MS and Digital Methods

I am interested in writing about three copies of the same item in the collection of Islamic material I am working on. This one particular text was originally composed the late 17th century in Persian and covers medical science; the three extant copies I have looked were written within two hundred years of the original. They differ across the main categories used to describe Islamic MS: historical (origin, content, provenance, etc.) and descriptive (script, binding, etc.) in a wide variety of ways. If the data they present can be mined and displayed properly, then various branches can spread out from them and encroach on a number of knowledge-spheres.

But I intend to approach the project in a new and different way, since my goal is to create various subject headings across these items. Traditionally, our ontology assumes a certain linear rigidity in the way we approach these items: study, list, and then compare the MS across these main categories. While this principle remains true and essential, it is also important to see how we display and learn from the information we can gather. In other words, our base assumptions of our ontology must be challenged and pushed, so as to turn the MS into an effective and dynamic pedagogical tool. This would mean not just listing the categories, but rather making them dynamic, versatile, and placed directly in the hands of the user. (here is a rough example; here is an article that discusses classification schemes in more detail).

This type of project requires preliminary preparation, including:

1. Perfect knowledge of the three copies at hand, including detailed historical, bibliographical, and descriptive data that covers important categories, including binding, paper, script, origin, provenance, content, etc.

2. Defining categories that are relevant and can extend beyond just the items under question; this again requires #1.

3. definite and ascertainable categories of definition that take into account the limitations of classification schemes and are open to further development.

4. permanent and stable classification schemes that can later be adjusted, and do not need to be radically re-defined.

5. history, history, history. Extensions into other knowledge-spheres might be initially limited, but such a project should be able to receive and sustain additional information that is incorporated into its classification scheme.

What I imagine is creating trees, charts, graphs, and other pedagogical tools through which the relevant categories can be tracked and studied. This does require some familiarity with digital tools and the current trends in digital humanities; in Islamic studies, DH is also a fairly recent development. Such a project, of course, will require collaboration between specialists in the digital world and the humanities.

Sourcebook on Islamic Scripts

I was able to find a comprehensive guide on all things Script (khat) recently. Scripts form a very important part of the historical and descriptive data of MS and I am interested in the genealogy and use of various scripts, their origins and periods/areas of popularity, and their evolution into formalized, popular, and desired expressions of scribal culture.

One excellent work on this is in Persian:

Talim-i Khat by Habib Allah Fazali (Tehran: Intisharat Surush, 1977). Here is the link to a free online copy.

Even though the book was written in the 70s, its description and comparison of various scripts and hands and the information it provided on their usage is valuable. It is intended as an instruction manual for students learning to write; it also reveals Fazali’s notions about six (6) different categories of people that engage in writing (ahl-i qalam wa nawisandigan). He lists the following:

1. Writers and Poets (muallifan wa shairan)

2. Writers of Newspapers (ruznameha), Articles (maqaleh), and Magazines (majjaleh). These groups, Fazali says, ‘come from various sectors of society’.

3. Copyists and Scribes (Munshiyan Wizaratkhaneha) that work for the government and official institutions (muassisat dawlati wa milli)

4. Copiers of Records and Authorities (Daftar Nawisan Asnad Nawisan); these work for courts and other registered institutions.

5. Painters and the like, who write on commercial boards and for advertisements. Fazali comments that they are concerned only with ‘water, color, and and expression’.

6. Scribes Proper (khattatan wa khushnawisan). Fazali claims to belong to this category and continues to extoll their virtues and qualities.

Further, Fazali has divided the book into ten (10) sections:

I Introduction

II On the Levels and Methods of Writing

III On Tools of Writing

IV General and Universal Rules of Scripts

V Specific Rules of the Four Hands: Thuluth, Naskh, Nastaliq, Shikasta

VI Specific Rules of Muhaqqaq, Rayhan, Thuluth, Tawaqi’, Naskh, Nastaliq

VII Comparison of Scripts (one of the most useful sections)

VIII Rules of Writing Persian

IX On Paper, Colors, Watermarks, and Marbled Paper

X Conclusion (khatima)

One of the most useful sections I found was VII, on the comparison of scripts. Here Fazali has presented an extensive table of initial, medial, and final shapes of all letters across 11 different scripts. This table provides one with a basic understanding of the scripts and their expression. In addition, the individual sections dedicated to each script provide detailed information about how each letter is formed, what sort of variants can be expected, and includes detailed instruction on the construction of each letter for each individual script. I was tracing the forms of the letter ya (ی) between Shikasta and Taliq scripts and I found that Fazali’s explanation helped me in deciphering the material.

In all, this a must have for those studying Islamic manuscripts in general and Persian manuscripts in particular. Fazali also reveals much about the conceptions of scribal culture, uses anecdotes from past scribes, and claims to extend the proper scribal etiquette from the past into the present.